I replaced the incandescent bulbs inside all the overhead dome lights with LEDs many years ago. I also use LEDs in the courtesy lights along the floor throughout the cabin, brass reading lights, and inside most of the wardrobe closets. Most of these LED lights were bought 10 years ago and none have needed to be replaced so far, making their extra cost well worth it.

I’ve been wanting to increase the lighting in the main cabin and decided on LED strip lighting. Through reading articles and reviews on the many different types and brands of LED strip lighting, I came up with the following list of features:

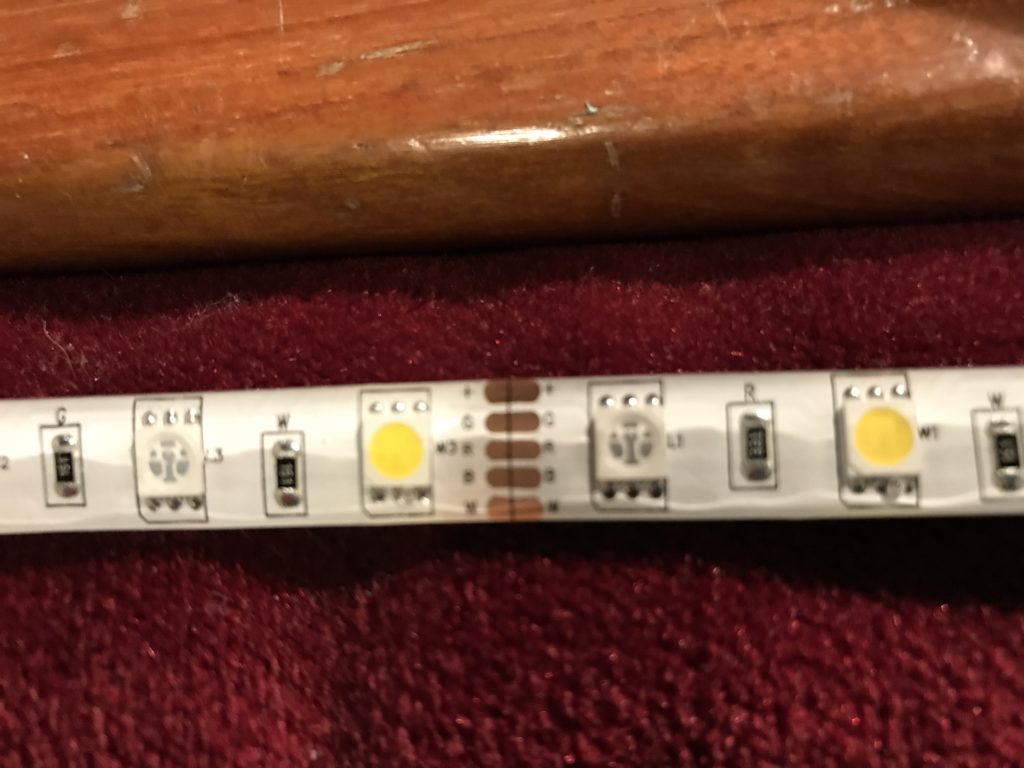

Color-RGBW stands for red, green, blue, white. This type has a RGB “cluster”, which are 3 closely-spaced LEDs that can produce millions of colors by varying the duty-cycle of each of the red, green, and blue LED individually, plus a separate white LED that can produce a warm white. In the strips that I ended up buying, the colored LEDs can be controlled separately from the white LEDs. Some LED strips are sold as RGB only, so the white is made by combining the red-green-blue and is not a true white (and definitely not a warm white).

Dimmable–most LED strips are dimmable. The ones that I bought have separate dimming for the colored LEDs and the white LEDs.

Remote controlled–I discovered there are many ways to control the strips–physical switch, remote control, phone app, and even Alexa control. I decided on a remote control.

DC Powered–Most kits I looked at were AC powered. Since I want to connect them to 12V, I made a DC adapter that powers the LED strips through a standard DC outlet. This gives me the option of powering them with AC or DC.

Misc.–Most LED strips are sold in 16′ rolls. Some are encased in a silicone sleeve to make them water resistant, a good idea for boat applications even they will be “indoors”.

Connectability–Not all LED strips have a connector on both ends, so running 2 strips in series is not possible (sell my first attempt below).

Layout on Boat-

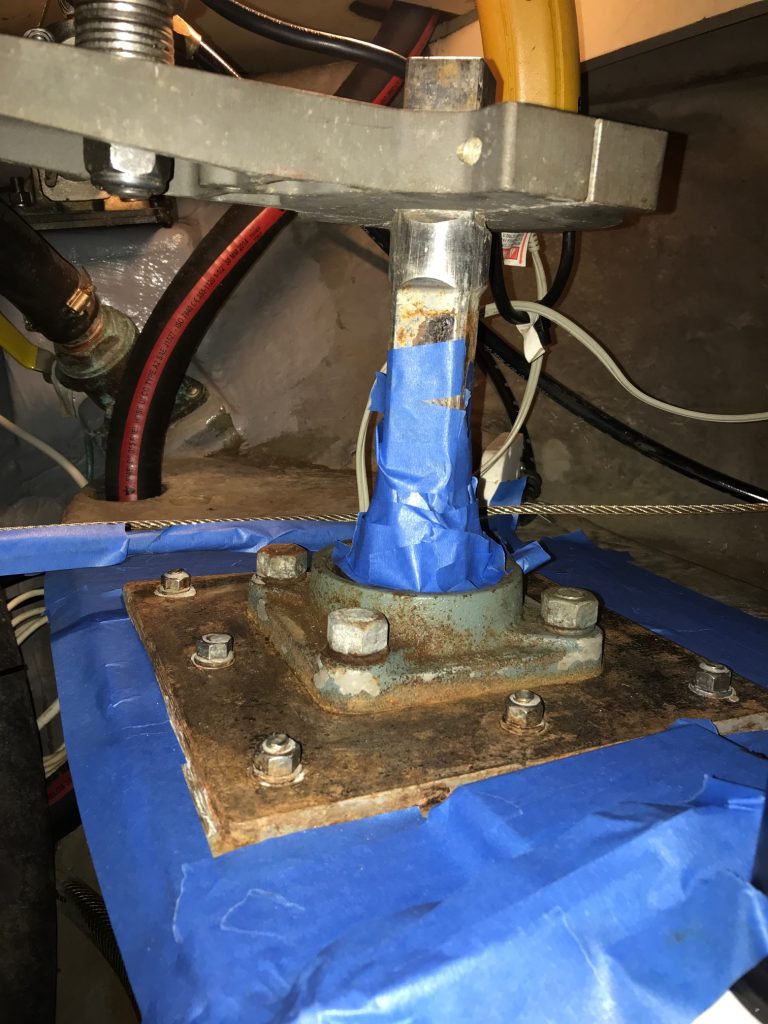

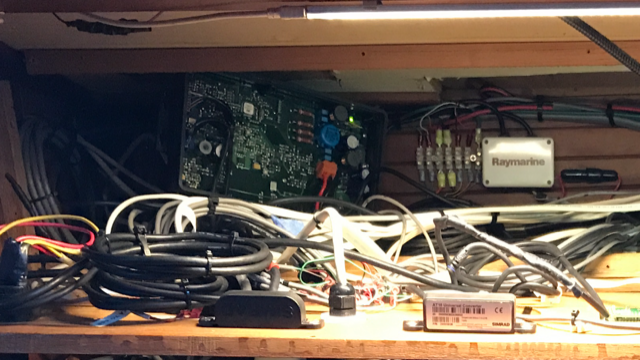

I wanted the LED strips not only for adding brighter lights to the main cabin, but also for adding colored and dimmed accent lighting. I also wanted the strips on port and starboard sides to be hidden from view as much as possible. As it turned out, a 16 foot long strip was just about the exact length from galley to forward bulkhead on port side, and nav station to bulkhead on starboard side. The main layout problem was to figure out how to run both LED strips with a single controller and where to place the controller.

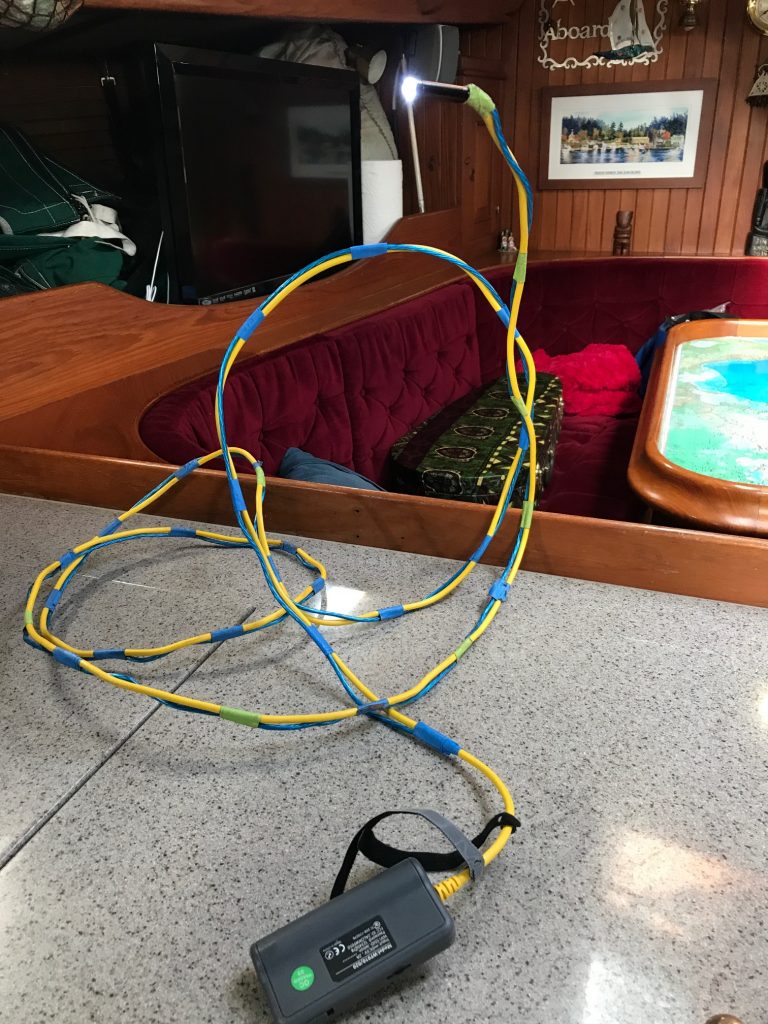

First Attempt: I ordered an LED set that contained 2 16′ RGBW strips, a controller with on/off switch and function control (brightness, color, mode). It was Alexa controllable (though that’s not a feature I would use on the boat) and came with a smart phone app for remote control. The controller output had a Y-connector that both strips were meant to plug into. This required me to modify the wiring by adding 12 feet of 4 strand wire to one of the legs to allow one of the strips to cross over from port to starboard along the cabin top. After soldering and heat shrinking both ends of the 12′ long 20 gauge wires, I discovered that the LED’s in the strip that the wire was added did not match the color or intensity of the LEDs in the other strip, probably due to the added resistance. I determined these would not work for the boat, so I removed the 12′ extension to get them back to the original lengths and found another use for them–my daughter’s bedroom!

Second Attempt: I researched and found another LED set that I thought would work better. It also contained 2 16′ long RGBW strips, a controller, and a remote. The main difference is that these strips had connectors on both ends and had a 5-wire bus vs a 4-wire bus. The reviews said that 2 16′ strips could be run in series. They also sold connector wire in 6′ lengths with pin connectors that matched the LED strips. This would allow me to run 1 strand on the starboard side, then add 12′ of extension wire in order to reach the beginning of the second strand on the port side. The 12′ extension did not affect the color or brightness of the second strip. Installing them was easy with the 3M tape attached to the under-side of the strips. I ran them along the back side of the wood trim so they are not visible. The remote works from anywhere in the main cabin. Here’s a link to these LEDs:

https://www.amazon.com/gp/product/B00JZKF2ZO/ref=ppx_yo_dt_b_asin_title_o07_s03?ie=UTF8&psc=1